With the reopening of the oil market in Brazil in 1997, it was expected that new private investments would be made in the sector. New investments were expected in the refining park and that competition would bring gains in quality and prices. In order for Petrobras and the private companies (Manguinhos and Ipiranga) to adapt to the free market, Law 9.478/97, known as the “Petroleum Law”, guaranteed a market reserve for a few years (Law 9.478/97, in its articles 69 to 74, allowed the creation of subsidies to private refineries and price and import controls by the Regulatory Agency for up to 5 years). This, in a way, would allow companies to transition to the competitive regime.

In fact, in a short time, there were some market movements that reinforced the initially imagined expectations. The Repsol YPF group, for example, acquired part of the control of the Manguinhos refinery. Later, it also acquired 30% of one of Petrobras' refineries, in Rio Grande do Sul. In addition, the Manguinhos and Ipiranga refineries proposed expansion plans for their units to the ANP. Two new private refineries emerged, Univen and Dax Oil. Sector restructuring and free competition seemed to be actually having the planned effect with the end of the monopoly. However, the following years showed that the difficulties for the private refineries were immense. A brief analysis of each of them, over the last decade, demonstrates the size of the challenge.

Maguinhos Refinery

Inaugurated in 1954, in the state of Rio de Janeiro (RJ), the Manguinhos Refinery was prevented from expanding its activities due to the state monopoly resulting from the creation of Petrobras, in 1953. As a result, its refining plant remained of low complexity and small size, when compared to the other refining plants existing in Brazil. Thus, it has always needed light oils for proper processing in its manufacturing facility. Until 1963, the refinery itself purchased imported light oil to meet its needs. From that year onwards, Petrobras also began to exercise a monopoly on the import of oil and derivatives, even starting to meet the needs of the private refinery, a situation that persisted until the early 2000s. Considering that the refinery survived the period of the monopoly, it is to be imagined that, throughout the period, it had some market reserve allowed by the successive Governments, because, otherwise, it would have been acquired by Petrobras, as happened with the refineries of Manaus (REMAN) and Capuava (RECAP ), or would have crashed at the time due to oil shocks and controlled prices in Brazil.

After 44 years of its operation, one year after the end of the monopoly of refining activities in the country, in 1998, the Spanish group Repsol YPF acquired part of the shares of Refinaria de Manguinhos, starting to share control of the unit with the former owner. , the Peixoto de Castro Group. With the promise of new investments, the partnership presented itself as an opportunity to leverage business at the refinery, although this did not happen in the following years.

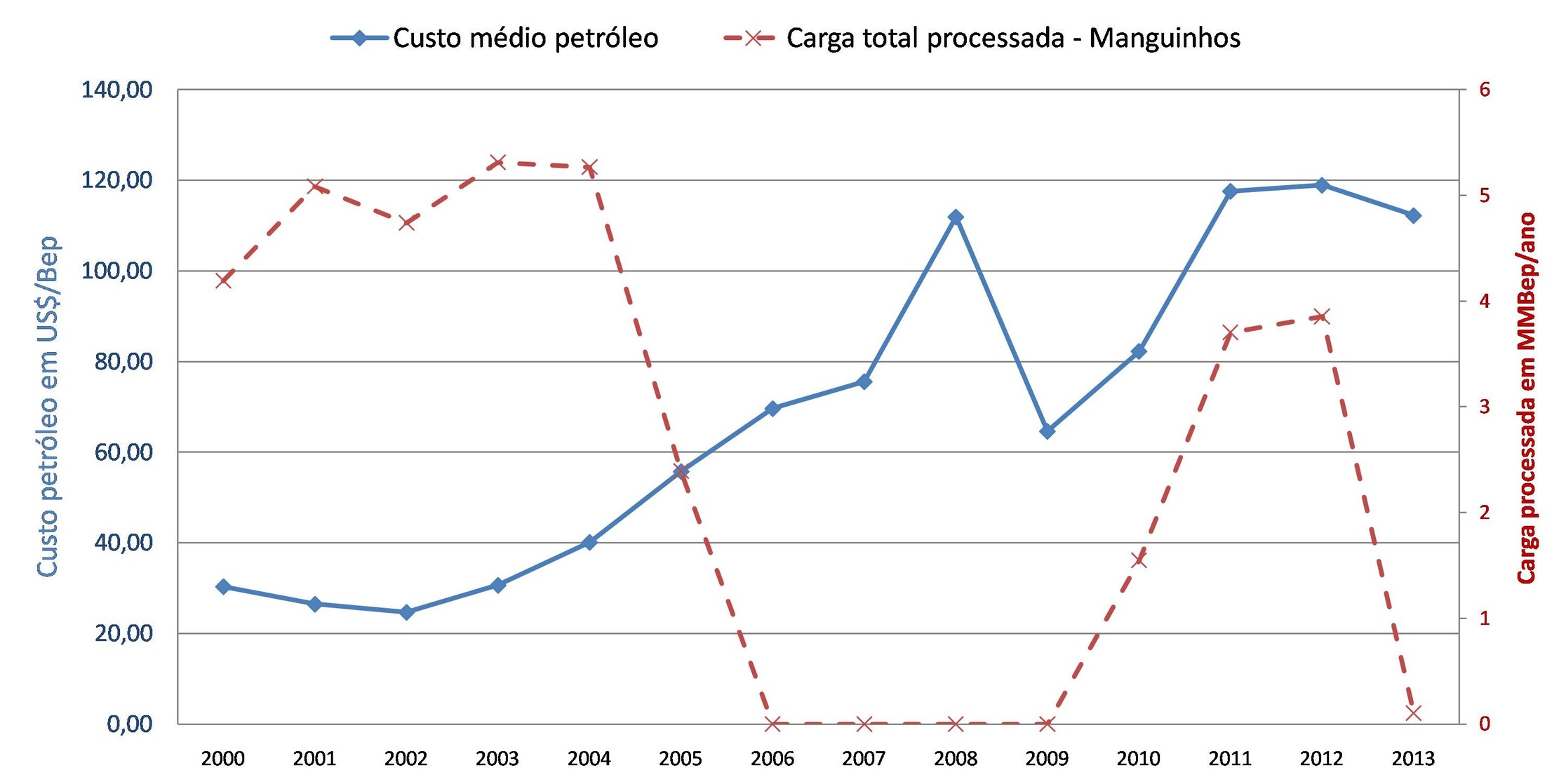

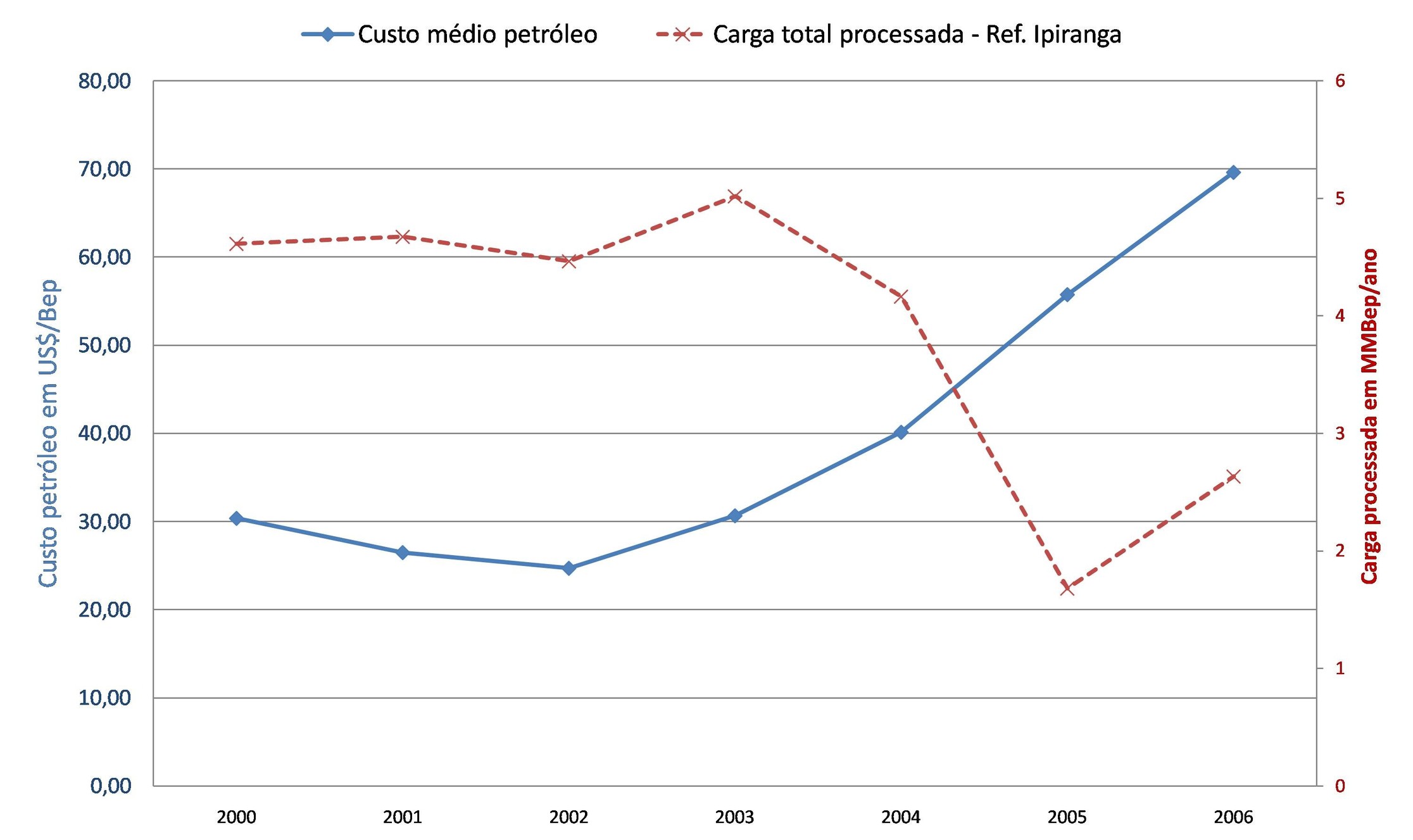

Investments, initially estimated by the new consortium, were reduced. There were several reasons. Repsol YPF started having difficulties in Argentina, which had already been in crisis for almost a decade, and the refinery's operating result was also never encouraging. The price of oil in the international market soared, making Manguinhos' refining margin negative, since fuel prices in the Brazilian domestic market were still defined by Petrobras, under the indirect control of the Federal Government, which held prices for long periods. periods, not transferring them in full to the final consumer. From 2004 onwards, the average price of oil on the foreign market began to rise steadily, causing the refinery's production to be completely interrupted in the years 2006 to 2009, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Average load processed in Manguinhos, in MMBep (million barrels of oil equivalent), and the relationship with the price of crude oil (Source: own elaboration based on ANP, 2017)

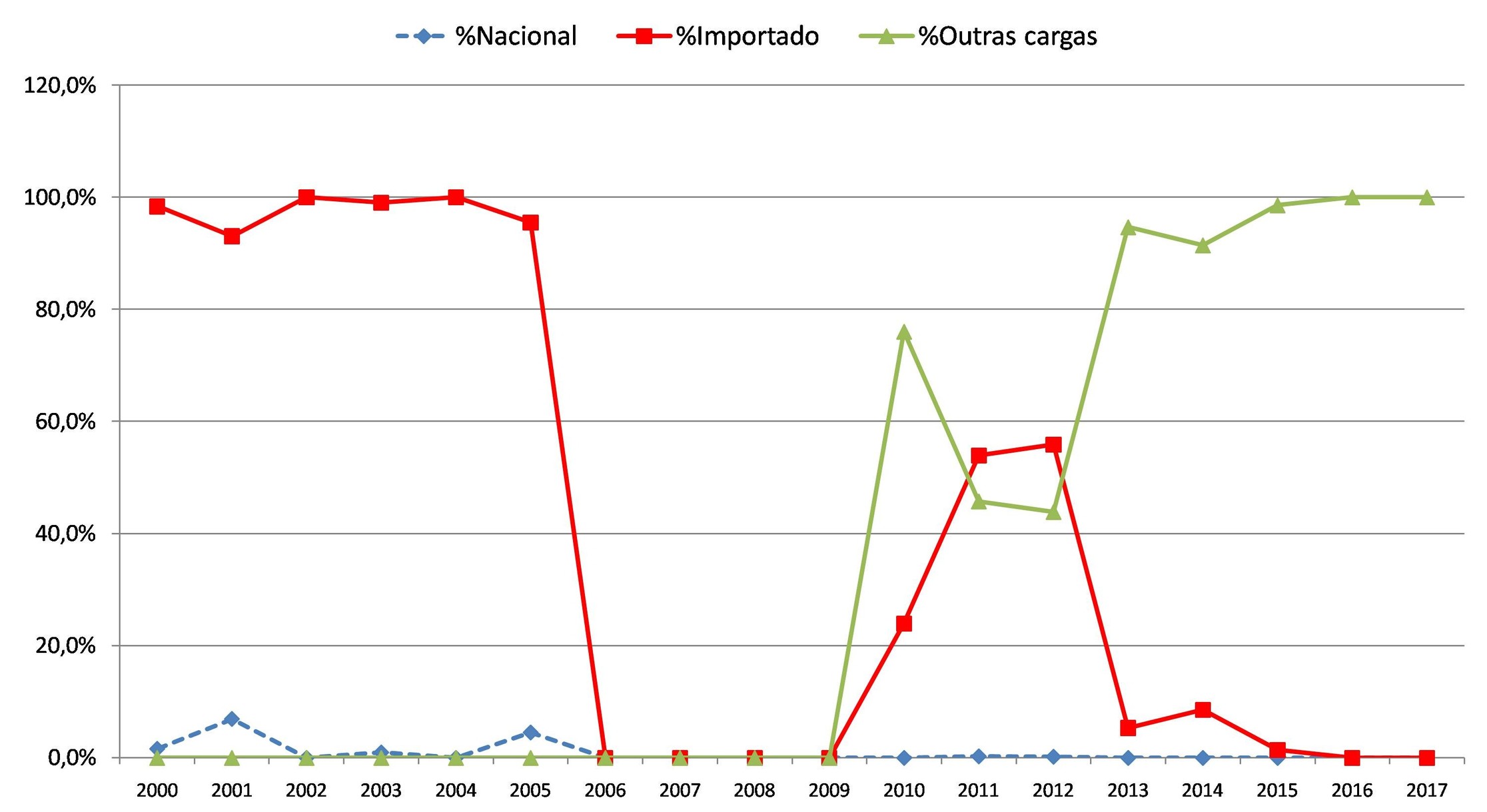

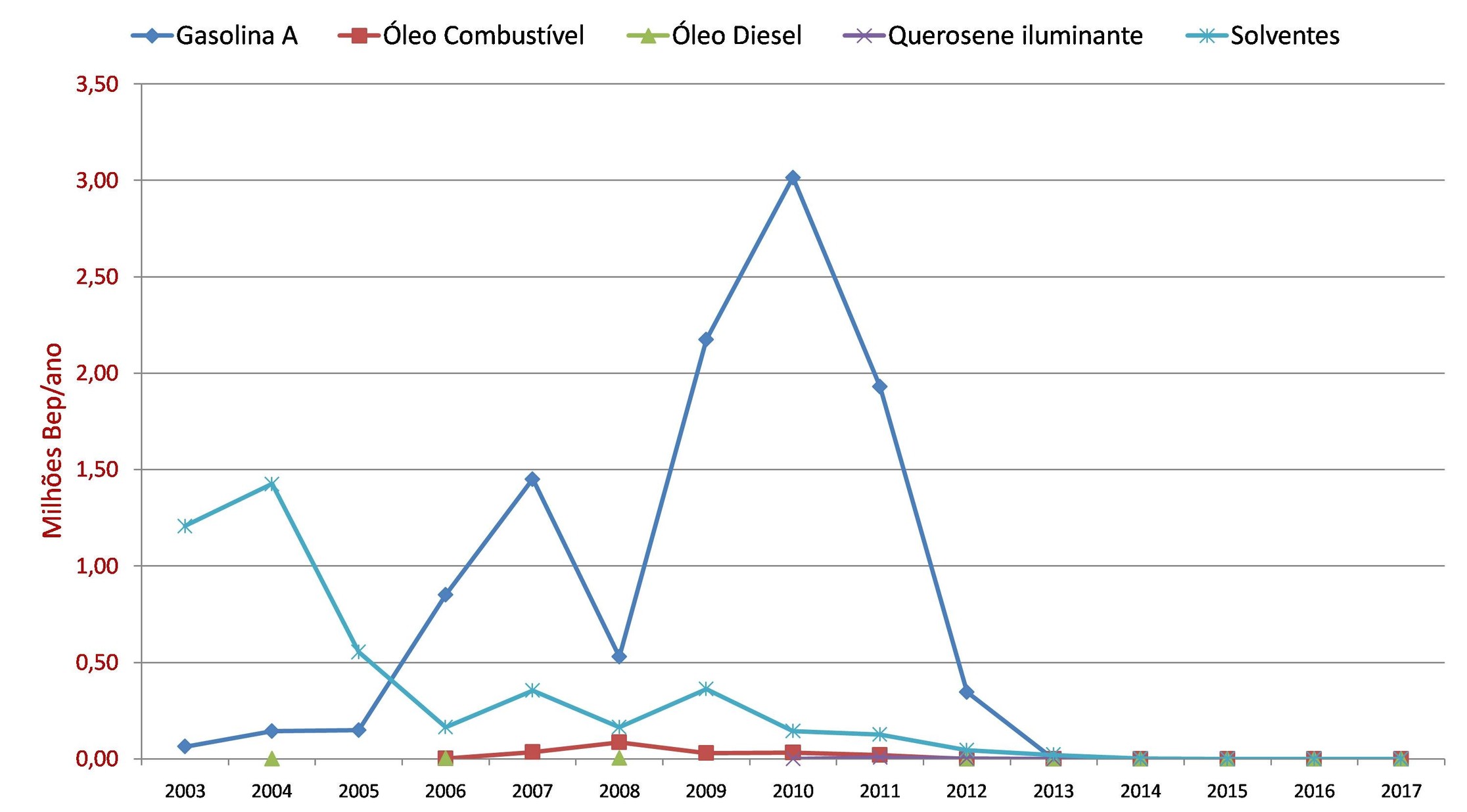

Failing to resist a serious financial crisis, the refinery entered into judicial recovery in 2008, when it was acquired by the Andrade Magro Group, which already operated in the chemical and fuel distribution segment. When it resumed operations in 2010, a downward trend in the use of oil was observed in subsequent years (Figure 2), until, from 2013 onwards, Manguinhos began to process other cargoes (naphtha and condensate, for example) as a way to to keep operating. Operating and financial results continued to be very poor and the refinery remained on the brink of bankruptcy. At the end of 2017, the refinery controller announced a change in the name of the unit, which is now called REFIT. Despite the name change, the challenges to refining oil were huge due to the refinery's age, size and technology. Possibly, today, the refinery is a more valuable asset as a fuel storage terminal than as an oil refining unit itself.

Figure 2 – Loads used in Manguinhos, in MMBep, from 2000 to 2016 (Source: own elaboration based on ANP, 2017)

Ipiranga Refinery

The Ipiranga Refinery began operations in 1937, having adjusted its shareholding control the following year, pursuant to CNP resolutions, which established that only native Brazilians could be shareholders of refineries in Brazil. Similar to what happened with the Manguinhos Refinery, after the institution of Petrobras' monopoly, Ipiranga's private concession was maintained, but it was also prevented from increasing its refining capacity throughout the period, being maintained, however, through its market reserve over the period.

The end of the monopoly in 1997, through Law 9.478, also guaranteed Ipiranga a market reserve for five years, so that it could prepare for free competition. In 1998, the ANP ratified the ownership and rights relating to Ipiranga's refining facilities, which existed at the time, with the refinery having a refining capacity of 12.500 barrels/day, based on existing operational capacity. Although it was prevented from expanding its activities during the monopoly, an important improvement was implemented at the Ipiranga Refinery in the 1970s, which was the installation of a Vacuum Distillation Unit. This gave Ipiranga slightly greater flexibility than the Manguinhos refinery (which only relied on atmospheric distillation), which allowed it to process slightly heavier (and cheaper) oils.

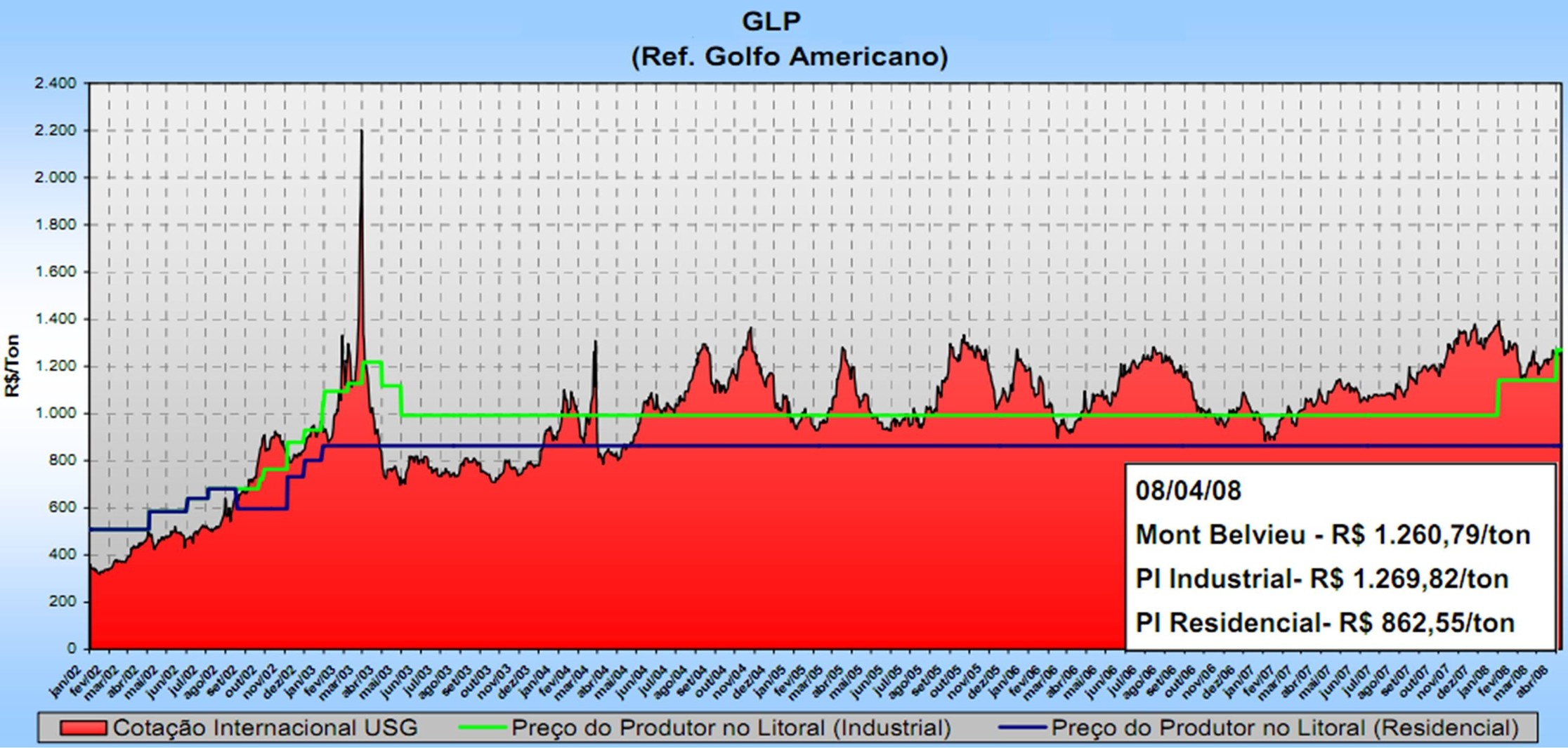

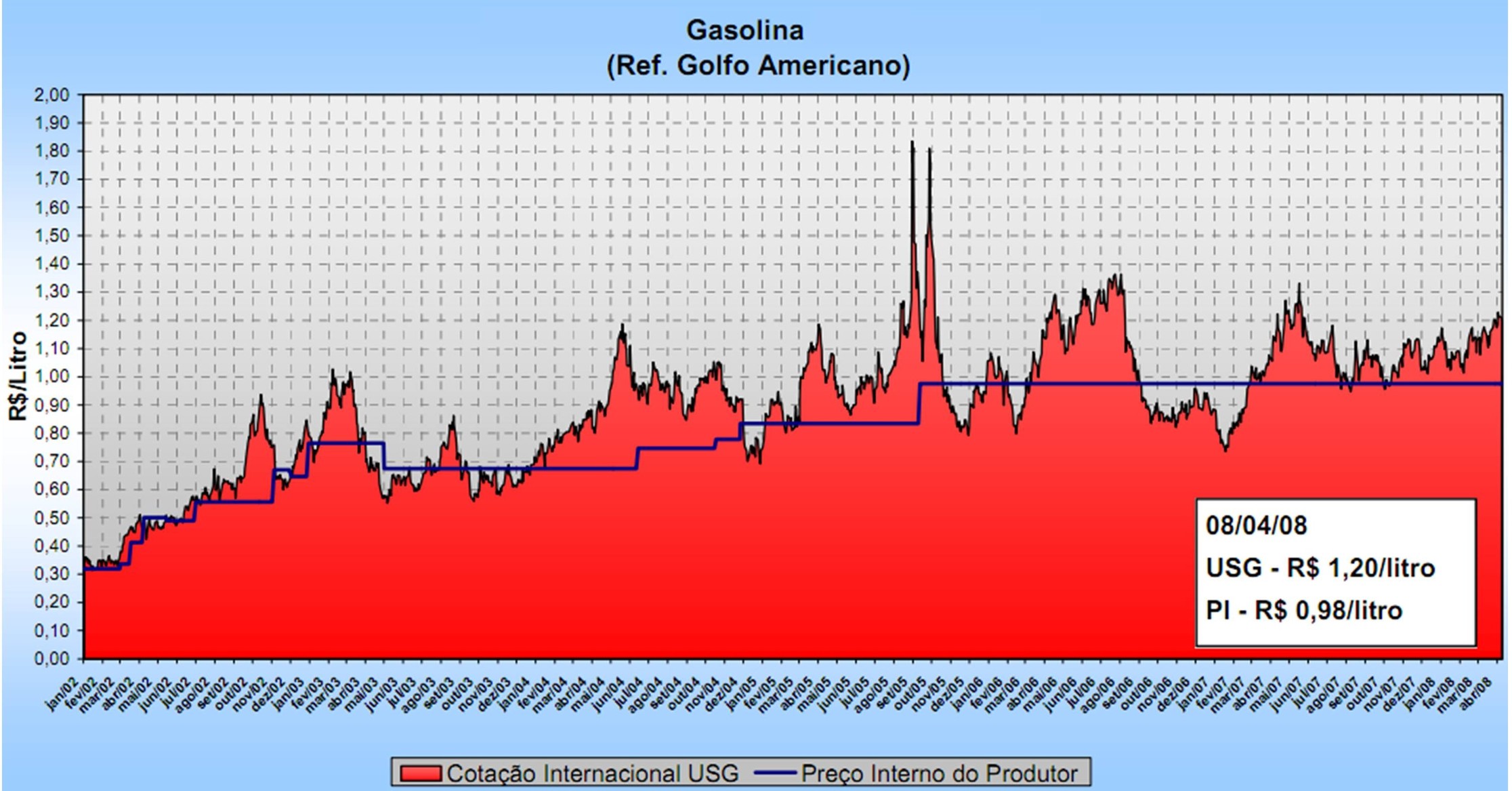

Envisioning growth and with an open market, Ipiranga asked the ANP to expand its refining capacity to 17.000 barrels/day, which was authorized and effectively carried out in 2002. In addition to increasing its capacity, the production profile was changed due to the possibility of using more suitable raw materials, with the direct importation of more than half of the oil consumed from the second half of 1999 onwards (RPR, 2014). Soon, however, difficulties arose due to the rise in oil prices in the international market, associated with the lag in the domestic prices of derivatives, mainly LPG, gasoline and diesel, which made up Ipiranga's portfolio. Figures 3 and 4 show LPG and gasoline prices, respectively, to illustrate the price lag registered from the end of 2003.

Figure 3 – Evolution of LPG quotations from 2002 to 2008 (Source: MME, 2008)

Chart analysis: it can be seen that from 2004 to 2008 the domestic price (IP) of residential and industrial LPG remained below the international quotation, demonstrating the state subsidy for this fuel in that period.

Figure 4 – Evolution of Gasoline quotations from 2002 to 2008. (Source: MME, 2008)

Chart analysis: it is observed that in several and long periods the domestic price (IP) of gasoline was below the international quotation. Although at times, the internal price was higher than the imported one, making clear the perception that it was under the state subsidy much longer.

Faced with this scenario, between 2003 and 2006, the refinery reduced its operations by almost half, registering a financial loss in its refining activity (RPR, 2014). The drop in production recorded in those years can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5 – Average load processed at the Ipiranga Refinery and the relationship with the price of crude oil (Source: own elaboration based on ANP, 2017)

In 2007, control of the Ipiranga Group, whose assets involved fuel distribution stations, petrochemical plants and the Ipiranga Refinery, was acquired by a consortium involving Petrobras, Ultrapar and Braskem. In 2009, the refinery was renamed Refinaria de Petróleo Riograndense (RPR), in which each of the three controlling partners now holds 33,3% of the shares of the corporate structure. From that moment on, the refinery operated with some profit in its operations, as Petrobras began to industrialize its own oil at times when the price of crude oil and derivatives brought losses to the unit. The future of this refinery is uncertain, due to the age of its facilities, load limitations and small size.

Two new small refineries appear: Univen and Dax Oil

Univen from São Paulo and Dax Oil from Bahia were two refineries created a few years after the opening of the oil market in Brazil. In order to occupy market niches or gaps left by Petrobras, they invested in small refining units, compared to the state-owned company's large refineries, to serve very specific markets with the production of special solvents. A model, incidentally, very common in the American market, which has more than 100 small refineries spread across the country (TAVARES, 2005). Despite the promising start, the same problems that other private refineries had soon appeared, exposed to the high price of oil on the international market and the control of fuel prices by the Brazilian Government.

Univen, a small refinery located in the city of Itupeva, São Paulo, was founded in 1992 and acquired by the Vibrapar group in 1997. Initially, it only produced hexane and, in 2001, its industrial park was expanded, starting to produce also other special solvents. In 2003, it was authorized by the ANP to process and refine light oils, petroleum condensate, naphtha and other petroleum fractions for the production of fuels and solvents (UNIVEN, 2014). In 2010, it was authorized to expand its processing plant from 6.919 barrels/day to 9.158 barrels/day (ANP, 2013).

Bahia's Dax Oil is also a small private refinery located in the Petrochemical Complex of Camaçari with a license to produce solvents since 2005, from the processing of naphtha and other petrochemical streams, being expanded in 2010 to a refining capacity of 2.095 barrels/ day (ANP, 2013). The unit was developed in partnership with the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA) and had the support of the Government of that State and the Association of Oil and Natural Gas Producers Extracted from Campos Marginais do Brasil (APPOM). It was a refinery designed to serve local production, allowing independent oil producers located in Bahia to market their oil production, which, being small, was not of interest to large companies.

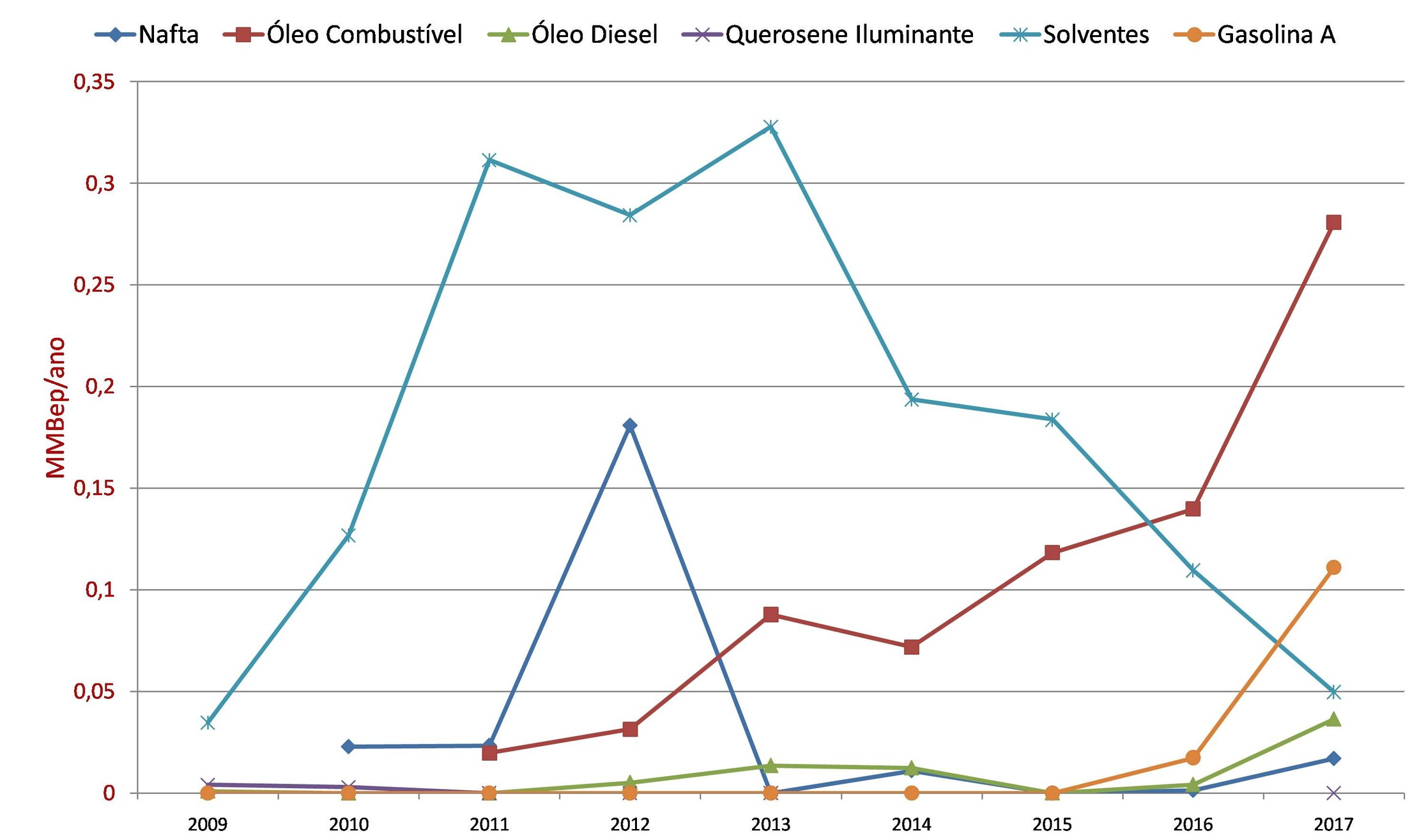

The two small refineries sought to adapt to market conditions. Univen, which initially produced more solvents at its unit, began to invest heavily in the production of gasoline from 2005 onwards (Figure 6), with one caveat: it used the same expedient adopted by Manguinhos, of paying the ICMS due to the tax authorities of São Paulo with precatorios from the government itself. Facing a lag in the domestic price of gasoline in relation to the international market, the rise in the dollar and the tightening of the São Paulo tax authorities in relation to the ICMS, it began to produce less and less of the fuel, until the unit stopped in 2012 (the controller, Vibrapar group, filed a request of bankruptcy and judicial recovery in that same year). Dax Oil, which initially produced solvents, began to invest more in the production of fuel oil (Figure 7), as a way of surviving in the market. The small refinery in Bahia continues to operate, unlike its similar refinery in São Paulo, which has not operated since 2012.

Figure 6 - Historical profile of derivatives produced by Univen (Source: own elaboration based on ANP, 2017)

Figure 7 - Historical profile of derivatives produced by Dax Oil (Source: own elaboration based on ANP, 2017)

The curious REFAP case

A curious case that well illustrates the difficulty of private refineries in Brazil is the joint-venture formed between Repsol YPF and Petrobras, in 2001, at the Alberto Pasqualini Refinery (REFAP), in RS. As previously mentioned, the Spanish Repsol, as a strategy to expand its business in South America, acquired the Argentine state-owned company YPF and part of the controlling interest in the Manguinhos Refinery (RJ), in Brazil. In 2001, in an asset swap with Petrobras, Repsol acquired 30% of Refinaria Alberto Pasqualini (REFAP), in an operation that involved some refining, petrochemical and gas station assets on Argentine soil in favor of the Brazilian state-owned company.

One of Petrobras' goals at the time was to go international and dominate the Southern Cone market. REFAP then became an independent corporation (S/A), a subsidiary of Petrobras. With the new partnership came investments to expand its oil processing capacity in the following years. Apparently, the Brazilian Government was interested, at the time, in using the same business model in other Petrobras refineries, following the liberal economic trend that began in the 1990s. then, in 2002, the government of then president Lula interrupted this trend.

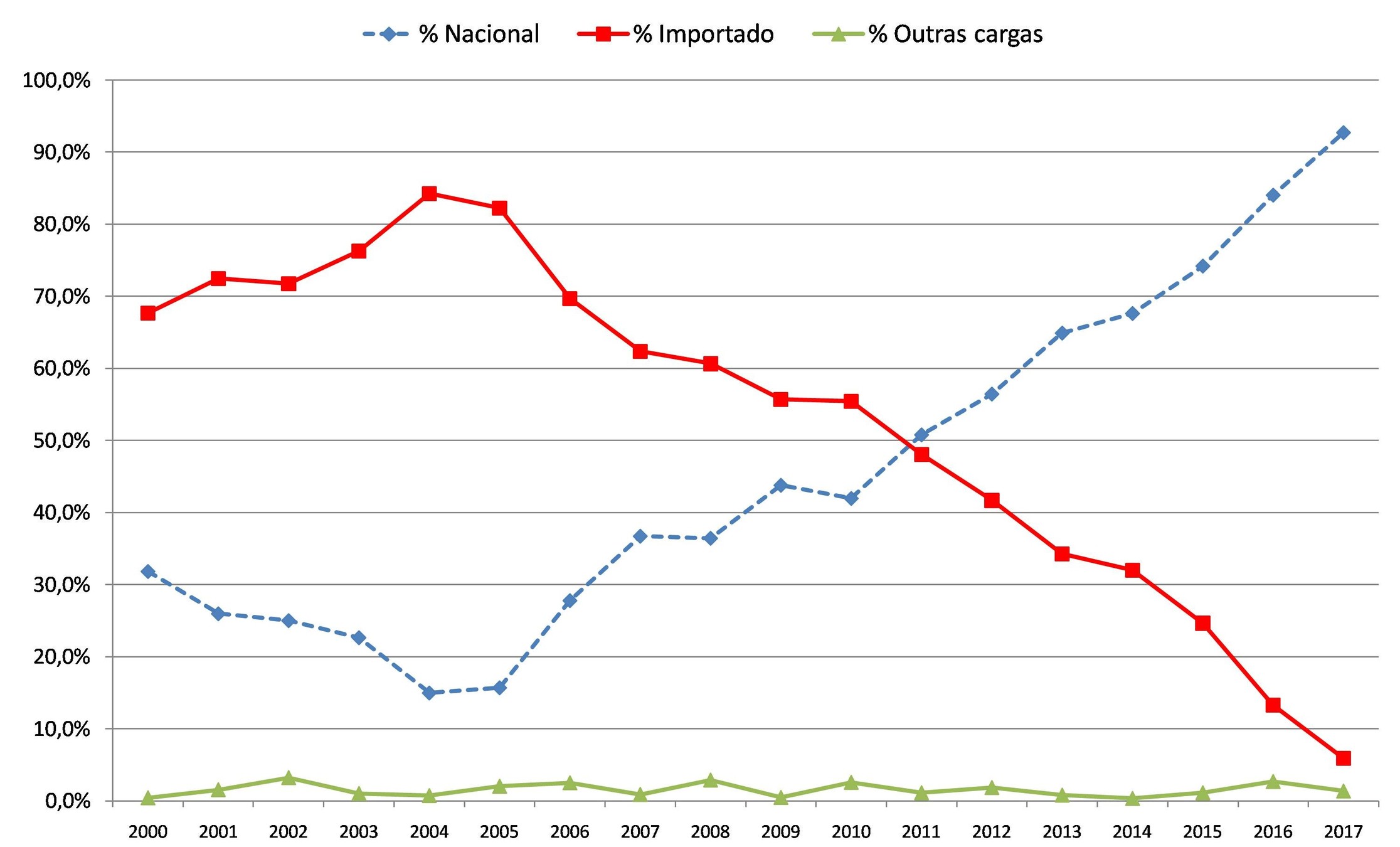

REFAP S/A, which at the time of its incorporation already used 70% of imported light oil in its refining unit, began to import even more in the following three years (Figure 8), reaching 84% of the processed load in 2004 The priority at that time would be to obtain the highest possible production of light derivatives, which are known to have greater added value. However, as already discussed, the price of a barrel of oil on the international market began to rise steadily from 2003 onwards, greatly burdening raw material costs, as occurred with other private refineries.

Com pesados investimentos para recuperar o chamado “fundo de barril”, para diminuir a dependência por petróleo leve importado, a REFAP inaugurou, em 2006, a sua unidade de Coqueamento ********* (UCR) e uma unidade de Craqueamento Catalítico de Resíduos (RFCC), o que permitiu adequar a sua unidade de refino ao petróleo brasileiro. Observa-se que, em 2011, a utilização de petróleo nacional ultrapassou o importado no blend of oils used by the refinery, and in 2016, the use of domestic oil curiously reached 84% of the load (same number registered in 2004 with imported oil).

Figure 8 - Oil profile used in REFAP (Source: own elaboration based on ANP, 2017)

Like the other private refineries, with the increase in oil prices, REFAP started to have negative refining margins. This is all associated with the need for successive investments to modernize its plant and demands for the production of better quality derivatives, with lower sulfur content. In view of this, at the end of 2010, after intense discussion regarding the need for new investments, whose partner did not agree, Petrobras announced the repurchase of 30% of the shares belonging to Repsol, returning the refinery to being 100% Petrobras again. This curious case of REFAP demonstrates the difficulty faced by private refineries in the country since the reopening of the oil market in Brazil 20 years ago. SOURCE Marcelo Antunes Gauto, Petrobras Industrial Chemist

I'm a driver.

Roberta, go back to school, please! No…

Premonition: whoever wrote this article is a…

The FA has the constitutional function of…

I'm happy when I see reports like this, it's...

This ship is subordinate to the Command of…

A pick-up can make any dream come true…

Nothing to do with it, it’s a transmission contract,…