Metallic wood came to revolutionize the world of industry! Discover the material used as membranes to separate biomaterials in cancer diagnostics, protective coatings and flexible sensors

Yes, there is already a wood harder than steel and titanium, but James Pikul, from the University of Pennsylvania, USA, wanted to invert the equation. So, instead of making wood that looks like metal, he made metal that looks like wood. The researchers have now finally managed to solve the biggest problem that prevented this highly promising metallic foam from being manufactured on a large scale: They managed to eliminate so-called “inverted cracks”, a type of defect that has plagued similar materials for decades.

Read also

- Macaé has many functions called for job openings in offshore construction and assembly contracts, today 8th of July

- Elementary, secondary and higher education job openings are open today (08/07) for work at an ethanol plant

- ExxonMobil, the largest oil company in the USA and operator of nine oil blocks in Sergipe, donates more than 287 thousand reais to fight the hunger of 3600 Sergipe families

- Loyalty to the brand at gas stations will end and the sale of fuel via delivery will be released; measure promises to reduce the price of gasoline by stimulating competition

- Brazilian multinational, world leader in foundry and metallurgical machining, in partnership with other global giants, develops the most efficient hydrogen internal combustion engine in the world

Despite technological advances in construction, wood remains a ubiquitous building material thanks to its high strength-to-density ratio.

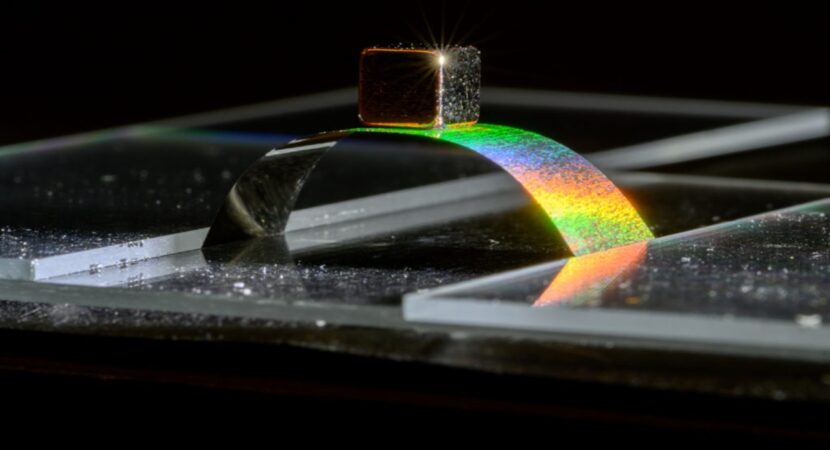

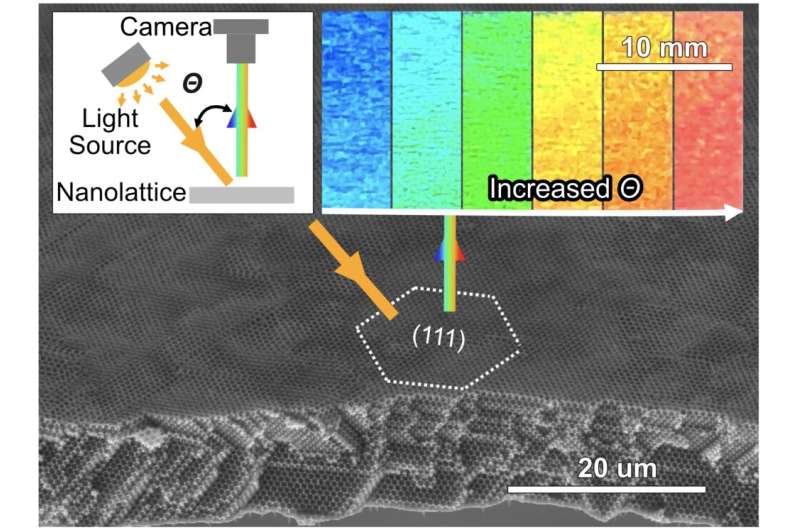

The precise spacing of these pores also gives the material some unique optical properties. The spaces between the gaps are the same size as visible light wavelengths, which means that light reflected from the wood interferes, with the result that specific colors – depending on the angle of reflection – are enhanced. This gives the material an attractive, shiny rainbow appearance, with the potential to be incorporated into sensing devices.

Although the material has been in development for several years, the engineers have solved a serious problem that has prevented them from making metallic wood in useful sizes: eliminating the inverted cracks that form as the material is grown from nanoparticles on metal films. Preventing these defects allows strips of the material to be grown in areas 20.000 times larger than before. The solution was detailed in a Nature Materials article.

When a crack forms in a conventional material, the bonds between atoms break, eventually causing the material to split apart. An inverted crack, however, is an excess of atoms. In the case of metallic wood, these are extra nickel atoms filling the nanopores that give it its unique properties.

"Inverted cracks have been a problem since the first synthesis of similar materials in the late 1990s," said graduate student Zhimin Jiang, who worked on the project. “Finding a simple way to eliminate them has been a longstanding hurdle in the field.”

Porous metal like wood and reverse cracks

Inverted cracks emerge from the way metallic wood is grown. It starts out as a “model” of stacked nanospheres. When nickel is deposited through the model, it forms a network around the spheres, which are subsequently dissolved to leave behind the nickel pore structure. However, the researchers found that if there are any places where the regular stacking pattern of the nanospheres is disrupted, the nickel will fill those gaps and produce an inverted crack when the model dissolves.

“The standard way to build these materials is to start with a nanoparticle solution and evaporate the water until the particles are dry and evenly stacked. The challenge is that the surface forces of the water are so strong that they tear apart the particles and form cracks, much like the cracks that form in dry sand," explained Professor James Pikul. “These cracks are very difficult to prevent in the structures we are trying to build, so we developed a new strategy that allows us to self-assemble the particles while keeping the model wet.

“This prevents the films from breaking, but because the particles are wet, we have to lock them in place using electrostatic forces so we can fill them with metal.”

Metallic wood is three times stronger than porous metals

Now that it's possible to create larger, more consistent strips of metallic wood, Pikul and his colleagues are particularly interested in using it to build new devices. He said: “Our new manufacturing approach allows us to make porous metals that are three times stronger than previous porous metals at similar relative density and 1.000 times larger than other nanolattices.

“We plan to use these materials to make a range of previously impossible devices, which we are already using as membranes to separate biomaterials in cancer diagnostics, protective coatings and flexible sensors.” says Pikul.

This work was partially supported by the pilot grant program of the Center for Innovation & Precision Dentistry at the University of Pennsylvania and by National Science Foundation under CAREER Grant #1943243.